More Information

Submitted: August 28, 2023 | Approved: September 04, 2023 | Published: September 05, 2023

How to cite this article: Nzayikorera J. Healthcare Bioethics: A Vital Branch of Bioethics and a New Possible Pillar for Modern Healthcare Systems Strengthening Worldwide. J Community Med Health Solut. 2023; 4: 063-075.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jcmhs.1001037

Copyright License: © 2023 Nzayikorera J. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Ethics; Bioethics; Healthcare; Branches of healthcare bioethics; Core principles and functions of healthcare bioethics; Healthcare bioethics systems; Pre-standard and standard practices in healthcare bioethics; Modern healthcare systems

Healthcare Bioethics: A Vital Branch of Bioethics and a New Possible Pillar for Modern Healthcare Systems Strengthening Worldwide

Janvier Nzayikorera*

Bushenge Hospital, Rwanda

*Address for Correspondence: Janvier Nzayikorera, Bushenge Hospital, Rwanda, Email: [email protected]

Globally, all people deserve the highest level of respect for their dignity, rights, and health. Bioethics has been recognized as a powerful discipline that aims to ensure such respect. Fritz Jar (1895–1953) and Van Rensselar Potter (1911–2001) will remain heroic men who ushered in the existence of the discipline of bioethics. Bioethics has been recognized as the science of survival and a bridge to the future. Thus, bioethics aims to enrich people’s wisdom. Wisdom is the knowledge of how to use knowledge for human survival and improvement in the quality of life. Worldwide, all people must widely possess such knowledge. Unfortunately, after many years of existence, implementing the principles and goals of bioethics remains centralized and confined to academic fields. Due to its centralized status, few branches of bioethics have been recognized. Besides, both pre-standard and standard practices still exist in the field of bioethics. Healthcare bioethical principles have been mentioned in numerous publications. However, healthcare bioethics has not been recognized as a vital branch of bioethics. The lack of well-established healthcare bioethics hinders strategies for eradicating many of the ephemeral and heuristic approaches that are still obstructing the achievement of optimum health status for numerous people worldwide. Integrating bioethical principles in all healthcare sectors in decentralized manners would lead to the existence of healthcare bioethics. The purpose of this manuscript is to describe healthcare bioethics as a vital branch of bioethics with respect to its description, branches, core principles, functions, system components, and pre-standard and standard practices of healthcare bioethics.

By November 15, 2022, the global population had reached 8 billion, and estimates show that it will reach around 8.5 billion in 2030, 9.7 billion in 2050, and 10.4 billion in 2100 [1]. Despite the anticipated rise of the global population, resources and other factors for supporting the global population to gain optimum health status and prosperous lives are in danger, as evidenced by unacceptable weaknesses in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals Worldwide at the mid-way point (2023) to 2030. Estimates indicate that by 2030, 575 million people will continue to live in extreme poverty, and one-third of nations will attain the aim of halving their particular national poverty rates. According to current trends, it will take 286 years to eliminate discriminatory laws and close the gender protection gap [2]. Astonishingly, in the field of education, the results of years of underfunding and learning losses are such that by 2030, over 84 million children will be out of school and 300 million children or young people who attend school will exit the school unable to read and write [2]. Unbelievably, food costs are still higher in many nations than they were between 2015 and 2019, and the world is once again experiencing starvation levels last witnessed in 2005 [2]. Therefore, despite an expected rise in the global population, many people will continue to live in dreadful conditions of health in the future. The possible major factors leading to this unfavorable progress include the continuous occurrence of abnormal climate change, conflicts, and wars between individuals, communities, and countries, the persistent existence of a higher burden of diseases, including the frequent occurrence of pandemics and epidemics, corruption and discrimination, etc. in various parts of the world. The main goal of bioethics is to ensure the genuine progress of science, people, and society [3]. Thus, the utmost use and proper application of bioethical principles, theories, and principles of ethics such as consequentialism and deontology, but also the Aristotelian principle (common sense and logic) in all countries and sectors in all actions, together with respecting the lives of other living things and bionetworks, is among the most powerful means to support the world’s people in being resilient to these unfavorable advances. Thus, more than ever, life for all and love of life (bioethics) are needed in order to achieve health for all on behalf of the current and future population. More than ever, science and technology are needed in order to ensure the survival of current and future generations of all living things. More than ever, ensuring proper interactions between biotic and abiotic factors is needed in order to achieve life for all and, in turn, health for all for the current and future human generations.

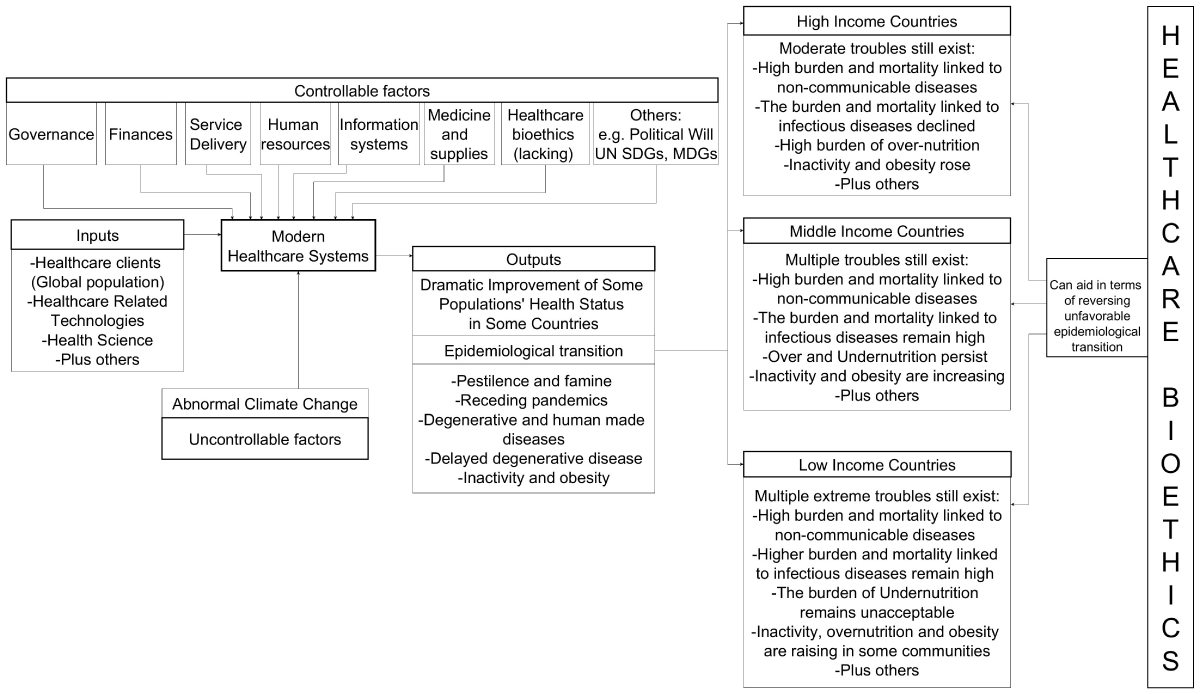

Modern healthcare systems have greatly improved as a result of the rapid advancement of science and technology. Figure 1 represents inputs, outputs, and controllable and uncontrollable factors that have led to the advancement of modern healthcare systems. Looking back, scientific and technological revolutions that have been occurring since the Renaissance era have trendily changed healthcare systems. Examples of passionate health-related scientists whose works helped pave the way for contemporary healthcare systems include William Harvey (1578–1657), Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), Ambrose Pare (1509–1590), Girolamo Fracastoro (1478–1553), Paracelsus (1493–1541), Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1519), John Hunter (1728–1793), Edward Anthony Jenner (1749–1823), Joseph Lister (1827–1922), Louis Pasteur (1822–1895), John Snow (1813–1858), Alexander Fleming (1881–1955) [4-8], plus others. Trendily, an epidemiologic shift in a number of diseases has occurred as a result of the use of new scientific discoveries in contemporary healthcare systems. Epidemiologic transition designates the trail of changes in the patterns of population age distributions, mortality, fertility, life expectancy, and causes of death in a given nation [9,10]. The epidemiologic transition can be described in five phases [11]. Phase 1 (pestilence and famine) is dominated by malnutrition and infectious diseases as the cause of death [9]. Higher children’s mortality and low mean life expectancy indicate this phase. Phase 2 (receding pandemics) comprises improving nutrition and public health services to result in a drop in the rates of deaths connected to malnutrition and infections [5]. Phase 3 (degenerative and human-made diseases) is discerned by augmented fat and caloric intake and a decrease in physical activities, leading to a higher prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), for instance, hypertension, diabetes, atherosclerosis, etc. Mortality linked to non-communicable diseases surpasses mortality from malnutrition and infectious diseases. Phase 4 (delayed degenerative disease) is marked by high morbidity and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases and cancers. The accessibility of better treatments and preventive efforts help to avoid deaths from these diseases. Phase 5 (inactivity and obesity) is marked by an upsurge of overweight and obesity at intolerable rates, coupled with increased rates of hypertension, diabetes, etc. Putting more efforts into preventive measures, for instance, reducing smoking rates and encouraging physical activity, can reduce the burden of diseases appearing in this phase. A favorable epidemiologic transition would have been homogenous worldwide if there were no differences in modern healthcare on a global scale.

Figure 1: Framework for integrating bioethical principles with various healthcare measures (1).

It is insupportable that diseases that appear in each phase of the epidemiologic transition are vastly prevalent in developing countries. Sub-Saharan African countries stay mostly in the first phase [12,13]. However, healthcare systems in these countries remain weak. Many blameless children continue to die due to undernutrition, and infectious diseases continue to be the most common cause of mortalities and morbidities in all age groups in Sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, NCDs have increased in Africa. The burden of NCDs in the member states of the African Union is higher than the world average, and between 1990 and 2017, sub-Saharan Africa had a 67% increase in the prevalence of NCDs [14]. By guaranteeing timely and affordable access to healthcare services, the deaths and morbidities associated with all of these diseases can be avoided. By 2023, malnutrition will remain a challenge worldwide, and it is affecting both city dwellers and countryside dwellers [15]. Despite the commitment to ending hunger everywhere in all of its forms by 2030, estimates show that about 600 million people will be chronically undernourished in 2030. The COVID-19 pandemic has proved that there are still many things to be done in terms of strengthening modern healthcare systems globally. Adopting the commitments of non-discriminatory healthcare-related policies is the most urgently needed approach in order to ensure homogenous and strong global modern healthcare systems. In the absence of healthcare bioethics, such commitments cannot be achieved. Food must be the focal point of bioethics’ logical considerations [16]. Without a doubt, if this reasoning is successful, malnutrition (both under- and over-nutrition) will be abolished on a global scale.

In the 1970s, the World Health Organization (WHO), under the leadership of Dr. Halfdan T. Mahler, set ambitious goals to achieve health for all by 2000 [3]. This ambition seemed to complement one of the four purposes of the UN: to help all people (especially poor people) live better lives, to conquer hunger, disease, and illiteracy, but also to encourage respect for each other’s rights and freedoms [https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/705254]. In the foreword of the World Health Statistics report (2019), Monitoring Health for SDGs, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus (a Director-General of the World Health Organization) emphasized that attaining the best quality of health for all people in all countries has been the World Health Organization’s (WHO) goal for 71 years [17]. Yet, health for all people has not been attained in all countries. In low-income nations, one out of every 41 women dies from pregnancy-related reasons, and each maternal death has a significant impact on the well-being of the surviving family members and the community’s ability to bounce back. Not only are the risks of maternal deaths increased by poverty, but their occurrence also keeps poor communities in a cycle of poverty from one generation to the next [17]. All these indicate that achieving health for all remains essential. Accordingly, ‘Dr. Mahler and others asserted that health for all must be a social and political goal, but above all, a battle cry to incite people to action [3]. Strategically, achieving health for all needs a strong health system in all countries [18]. The health system refers to all organizations, people, and actions whose primary intent is to promote, restore, or maintain health. Intuitively, integrating all principles of bioethics within all healthcare sectors is among the most powerful and cheapest approaches that could support all countries in strengthening their health systems because such approaches can empower all people to take actions that are in line of upgrading means of livings with productive lives.

Due to the relevancy of bioethics in terms of respecting humans’ dignity, health, and rights, in 2002, UNESCO’s Director General established an Inter-Agency Committee on Bioethics of the United Nations [19]. Bioethics is a fairly new discipline that aims to raise wisdom for human survival and to upgrade the quality of life because wisdom is recognized as the ability to apply knowledge to enhance the quality of life and ensure human survival [20,21]. Such knowledge must reach all people worldwide. If such knowledge is driven and well perceived by a global population, it would support most of the international organizations (especially WHO and UNESCO) and various nations in achieving some of their mandates. Unfortunately, after many years of the existence of bioethics, implementing its principles and goals somehow remains centralized and confined to a few academic fields. Integrating all bioethical principles in all healthcare sectors in decentralized manners would form healthcare bioethics. Healthcare bioethics can help eradicate or minimize numerous ephemeral and heuristic approaches that are still obstructing the achievement of optimum health status for some of the global population. However, no investigator has thoroughly described healthcare bioethics as a vital branch of bioethics. The purpose of this synthetic article is to describe healthcare bioethics as a significant branch of bioethics with respect to its description, branches, core principles, functions, components of the healthcare bioethics system, and pre-standard and standard practices in healthcare bioethics.

Description of healthcare bioethics

Health is a crucial fundamental human right [22–24] and an indicator of respecting the life and dignity of all people. Article 14 of the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights focuses on social responsibility and health as one of the means for supporting the UN and all world nations to achieve their ambitions for sustaining the highest level of human dignity, rights, and optimum health status. Point 1 of this article emphasizes that “the promotion of health and social development for their people is a central purpose of governments that all sectors of society share [19,25]. All people in all countries deserve healthy lives and well-being [26]. However, people should not be passive beneficiaries in terms of attaining such an optimum health status; rather, they must actively participate in all actions that aim to ensure the attainment of such a high level of optimum health status. In order to achieve that, people need knowledge and wisdom. UN agencies, especially UNESCO and WHO, have recognized bioethics as a discipline to aid in the sustenance of the highest degree of human dignity and the health status of the global population. In 2009, the WHO organization established the Global Network of WHO Collaborating Centers for Bioethics [27]. The mission of such a network is “to support the three levels of WHO (headquarters, regional offices, and country offices) to implement its mandated work in the field of health ethics and governance, which relates to one of WHO’s core functions, namely articulating ethical and evidence-based policy” [28]. This network focuses on global health ethics and it targets academic centers. Global health ethics must include handling transnational health-related ethical issues. However, such appears to be a centralized approach, as there is no emphasis on how to disseminate bioethical knowledge to enable the entire world’s population to improve their quality of life. In fact, such a network does not have representatives in all countries in the world. Thus, essential elements have been missed. In order to enable all people to appreciate the benefits of bioethics, there must be top-down and bottom-up approaches to delivering bioethical knowledge to all global populations. Establishing healthcare bioethics can do better in terms of delivering such knowledge to all people.

Healthcare bioethics must be uniquely recognized as a branch of bioethics that focuses on the application of ethical principles as a mechanism of wisdom enhancement in regard to dialogues and decision-making related to healthcare events and situations. Such dialogues should scrutinize not only facts and statuses adjoining each event but also standards that prime all healthcare-related clients, healthcare teams, and institutions deciding to recommend, accept, or refuse certain demeanors. Healthcare clients encompass all human beings (i.e., healthy and sick ones, born and unborn, including the human zygote or embryo, young and elders, rich and poor, educated and non-educated, males and females, etc.). The most important health event that all people deserve is to survive with minimal or no compromises. Healthcare teams and institutions encompass all those people and institutions dedicated to maintaining and restoring health. In order to establish healthcare bioethics, all bioethical principles must be integrated into all healthcare sectors. Moreover, great consideration should be given to ensuring the proper interactions of abiotic and biotic factors because they are major determinants of life and health. All activities taking place in healthcare bioethics must be monitored and recorded to assess the extent of implementation and enable improvement strategies. There must be a healthcare bioethical system to ensure the sustainability and comprehensibility of activities that take place in healthcare bioethics.

Branches of healthcare bioethics

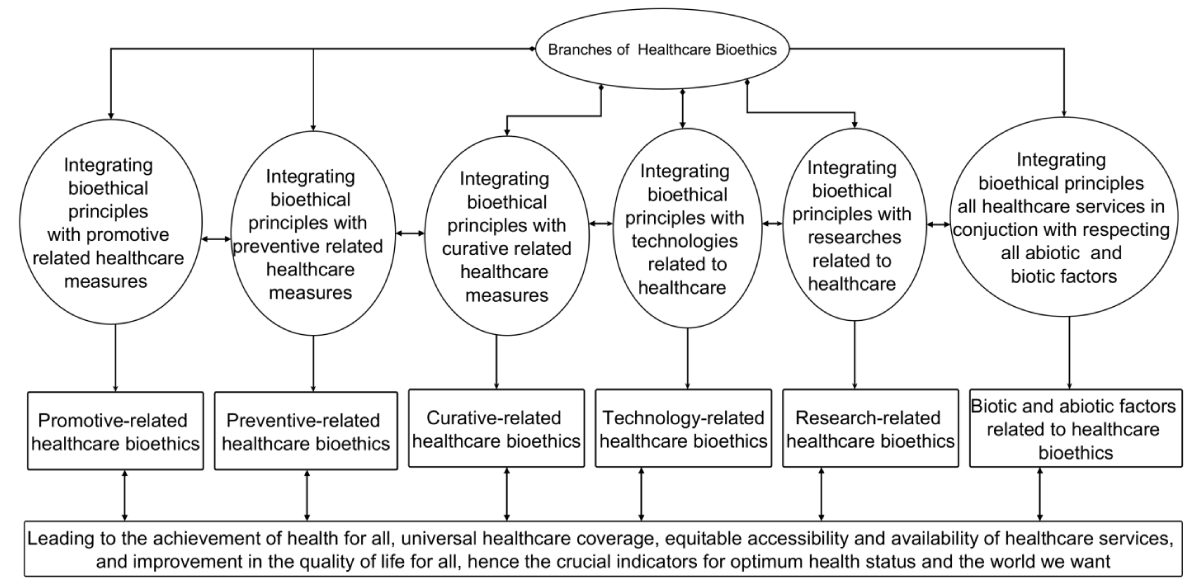

Having knowledge about the branches of healthcare bioethics is essential because such knowledge can support planning, implementing, monitoring, and forecasting all activities that take place in healthcare bioethics. Generally, healthcare has three components, namely: 1) provision of health promotion measures; 2) provision of preventive measures; and 3) provision of curative measures. Moreover, technologies, research, and respect for abiotic and biotic factors are essential elements that support the delivery of healthcare. As it is shown in Figure 2, integrating bioethical principles with these components leads to six branches of healthcare bioethics, namely: 1) promotional-related healthcare bioethics; 2) preventive-related healthcare bioethics; 3) curative-related healthcare bioethics; 4) technology-related healthcare bioethics; 5) research-related healthcare bioethics; and 6) respecting biotic and abiotic factors-related healthcare bioethics. The first two and third may be termed public health bioethics, and clinical bioethics, respectively.

Figure 2: The components of Healthcare Bioethics System.

Core principles of healthcare bioethics

In ancient times, Hippocrates initiated modern medicine and medical ethics [29,30]. For subsequent centuries, four core principles of medical ethics, namely: 1) autonomy, 2) beneficence, 3) non-maleficence, and 4) justice, came into recognition [31,32]. Globally, the core principles of medical ethics are crucial because they may act as focal guiding points to aid in dialogues and decision-making related to planning, monitoring, implementing, and forecasting all activities that aim to respect all humans’ dignity, rights, and health. Thus, these principles should be used as mechanisms of wisdom enhancement to improve people’s health and well-being.

Autonomy: Autonomy is the core principle of ethics. Veracity, privacy, and informed consent are the three components of autonomy, and they have distinct explanations and applications. Veracity is about telling the truth to the self-contained brain and the brains of others. Veracity has been mainly explained in the context of patient-physician relationships. However, veracity should be applied at all levels of the healthcare sectors (micro, meso, and macro). At the micro-level of healthcare sectors, healthcare clients should be the primary implementers of veracity through the adoption of moral conduct that promotes their lives and well-being. Achieving that would indicate truth-telling to the self-contained brain because the majority of us want better health status, and that is what we tell our brain all the time. Healthcare teams are core promoters of health and healers. They should apply veracity at any interface between them and their clients in order to maximize the outcomes of their interventions. Healthcare facilities should also apply veracity while implementing health policies, either those set by central healthcare organizations or those set by healthcare facilities. The meso-level of the healthcare sector is composed of interconnections between central healthcare organizations and peripheral healthcare organizations and between peripheral organizations and clients [33]. Whereas the macro-level of the healthcare sector is formed by multi-interpartnerships between countries and international healthcare-related organizations such as the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), etc., but also by partnerships between countries themselves. Health-related policies are mainly made at these levels. Most of those policies are in line with strengthening the health system with the aim of resulting in maximal health status for all people. Making any healthcare-related policies indicates the promise to all healthcare-related clients that they deserve healthy lives and well-being. Without any excuse, such policies should be implemented. It is an obligation for countries to ensure the best health status for all of their citizens [34]. The apparent veracity at the meso and macro levels of the healthcare sector may be marked by the successful implementation of goals and actions set in health-related policies. The triumph of maximum health status for all people at the national and global levels would be a marker for the existence of a stronger health system. However, a weak health system still exists in many countries, probably due to the existence of deceiving implementation strategies for health-related policies. Not only do deceiving practices affect humans’ lives, but other forms of life have also been affected. For instance, abnormal climate change continues to negatively affect all forms of life. However, policies that aim to tackle abnormal climate change are still suboptimal. To reverse all these, globally, veracity and other ethical principles should be integrated into all policy implementation strategies to serve as a means of optimizing health status and respecting other forms of life [35].

Privacy and informed consent are crucial components of healthcare bioethics because they aim to respect humans’ dignity, rights, and health [36]. Informed consent focuses on self-determination for any healthcare-related interventions and on accepting to participate in any health-related research [32,37]. Healthcare clients have the right to refuse or accept certain treatments or other interventions. However, such becomes applicable when the clients are conscious when they have reached maturity age, and when they have the capacity to reach the healthcare facilities to receive the care. Classically, many clients are willing to give consent as long as good relationships between them and healthcare professionals have been established and their privacy is maximally ensured. The painful facts remain for those clients who cannot reach healthcare facilities. Moreover, those with the capacity to reach healthcare facilities but healthcare providers are insufficient. A classic example is found in the surgical field. In 2015, the Global Lancet Commission on Surgery affirmed that worldwide, about 5 billion people lack access to safe, inexpensive anesthetic and surgical care [38-40]. Nine out of 10 people cannot access basic surgical treatment in low- and lower-middle-income nations. Most of those surgical clients are willing to give consent because most of them are in severe pain, disabled, or have body disfigurations. What has been lacking is, to meet present and projected population demands, sufficient investment in human and physical resources for surgical and anesthesia care services. Healthcare bioethics would support tackling these unfavorable medical access issues because one of the aims of Article 2 proclaimed in the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights is ‘to encourage equitable access to medical, scientific, and technological advancements, as well as the greatest flow and the fastest sharing of knowledge regarding those advancements and the sharing of benefits, with a focus on the needs of developing countries [19]. This aim should be synergistically used as a means of wisdom enhancement to ensure timely management of all medical conditions, including surgical conditions. Respecting patient privacy would also enhance patient wisdom related to giving consent, not only in the medical field but also in health-related research.

Beneficence: The world is still dealing with unfinished business because ensuring healthy and prosperous lives has not been achieved globally. Techno-scientific knowledge can support the achievement of various global ambitions if used properly and equitably. Article 4 of the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights is concerned with the benefit and harm principle, and it proclaims that “in applying and advancing scientific knowledge, medical practice, and associated technologies, direct and indirect benefits to patients, research participants, and other affected individuals should be maximized and any possible harm to such individuals should be minimized” [19,25]. Moreover, protecting the interests of current and future generations is one of the main purposes of bioethics. The Millennium Development Goals, set in 2000, will remain crucial until 3000. Firmly, the use of beneficence in healthcare bioethics, and other fields can support current and future generations in achieving the MDGs because beneficence aligns with the goals of respecting humans’ dignity, rights, and health.

Non-maleficence (do not harm): Non-maleficence has mainly focused on ensuring the painless treatment of clients who come into contact with medical practice. However, do not harm is a broader and essential principle; in fact, it is the most needed wisdom to support people to gain a quality life and live in a better world. For instance, the do not harm principle should be used to promote peace comprehensively worldwide to result in the avoidance and reduction of conflicts and wars between individuals, groups, communities, and countries. Non-maleficence should be used to empower all people to not adopt anything or behaviors that are likely to harm their health. It should also be used in terms of encouraging all people to stop doing activities that emit greenhouse gases into the atmosphere to result in the eradication of ecosystem destruction and slow down the likelihood of the occurrence of abnormal climate change. Do not harm should be applied to ensure that every scientific activity and technology is in line with protecting ecosystems and thus supporting the progression of life for all living things in shared appreciation of the benefits one living thing brings to another.

Justice: Scientific knowledge and technologies of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have dramatically advanced. The advancement of medical-related scientific knowledge and technologies has led to improvements in the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of numerous diseases. However, due to the existence of inequalities and other factors, numerous people still do not optimally benefit from such technologies and knowledge. For illustration, by the 1940s, dialysis technologies had become available; these lifesaving, innovative medical technologies, together with others, came with many ethical dilemmas related to the distribution of scarce resources. Such dilemmas have not been fixed today because, for instance, in low- and lower-income countries, patients who need dialysis do not have the opportunity to access them. Most of them die quickly, yet the availability of dialysis services would extend their lives. In September 2000, the UN proclaimed 8 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) that were to be achieved in 2015 [41]; however, this was an incorrect description in relation to timing because the millennium that started in 2001 will end in 3000. On September 25, 2015, the UN declared 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with 169 targets to be achieved by 2030. The main goal of the SDGs is to transform our world by securing a better future without leaving anyone behind [42]. Setting ambitious actions for securing a better future must go hand in hand with ensuring genuine progress in science and technology, for which outcomes must be justly distributed to all people and society. Thus, the principle of justice should be reinforced universally. Justice will remain the core compass to guide achieving the MDGs until 3000. Fundamental equality for all people in terms of their rights and dignity must be upheld so that they get just and equitable treatment.

Components of the healthcare bioethics system

The author wishes to comprehensively describe the components of the healthcare bioethics system. Widely, these descriptions pinpoint all features that are of considerable interest in terms of combining techno-scientific knowledge with moral issues in order to maximize humans’ health, dignity, and rights. Since the inception of bioethics, numerous authors and organizations have expressed an interest in it. One of the outcomes of those authors and organizations has been the publication of uncountable works. They sympathetically made their manuscripts, books, and reports accessible to us in advance in various publications. However, most of their works seem to narrowly focus on ethical issues that arise from daily clinical practices and research fields. No further accounts have been given to describing bioethical knowledge, theories, and practices as mechanisms of wisdom enhancement that can result in the improvement of people’s health and well-being. Global bioethics has also been established, but it has been criticized for not being a sufficiently unified field [43], partly due to a lack of thorough descriptions of its elements. In the author’s opinion, such a lack leads to unsatisfactory outcomes for some branches related to global bioethics, which may also negatively affect healthcare bioethics.

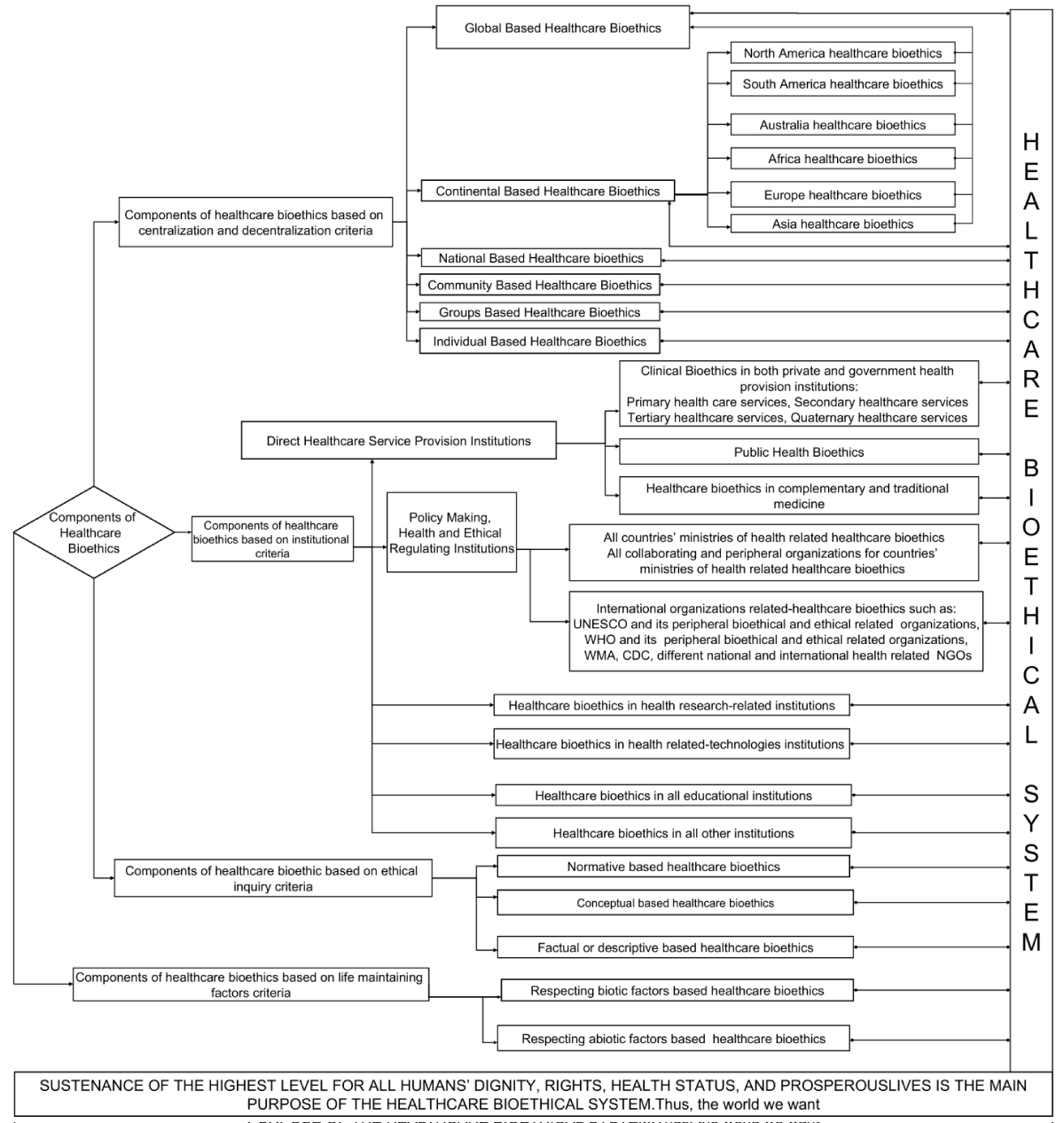

Hitherto, there are no homogeneous ways to understand all ethical dilemmas and health-related problems that have been affecting the global population because each individual, community, country, and continent possesses unique moral principles that guide their actions. Ethical questions related to health, health care, and public health cover topics as diverse as moral issues surrounding individuals in ensuring healthy lives, community ambitions for ensuring healthy communities, healthcare providers obligations in the provision of effective and efficient healthcare services to their clients, state obligations in the provision of health care services, appropriate measures to control all diseases, appropriate measures to ensure advancement of technology and science without destroying people’s health, etc. The spectrum and mechanisms for understanding those moral issues are diverse from one region to another, from person to person, etc. Despite such diversity, it should be emphasized that those moral issues must be probed properly and integrated with scientific facts to improve the health status and well-being of the global population. Pooling moral issues and scientific facts would be the best approach for creating bioethical knowledge to help people improve their quality of life. Accomplishing that would make a healthcare bioethical system. Though not exhaustive, using four criteria: 1) centralized and decentralized-based criteria; 2) institutional-based criteria; 3) ethical inquiry-based criteria; and 4) life-sustaining factors-based criteria The components of the healthcare bioethical system are shown in Figure 3. All components of the healthcare bioethics system should be used to enable the attainment of prosperous lives and the highest level of dignity for the global population.

Figure 3: Showing the components of the Healthcare bioethics systems.

Centralization and decentralization criteria: Given that healthcare, and bioethics apply to all humankind [3]—educated and uneducated, males and females, affluent and poor, sick and healthy, residents of developed and developing nations, etc.—centralization and decentralization criteria are taken into consideration. In order to enlighten everyone on the planet, the objectives of healthcare bioethics need not necessarily be implemented in centralized but rather decentralized ways. Figure 3 displays the elements that make up the healthcare bioethical system in descending order. The highest level is represented by bioethics in global healthcare. The order emphasizes that healthcare bioethical information should be enforced and widely disseminated from the global level to the individual level, even though individual-based healthcare bioethics appears at the lowest level. This order coincides with decentralized approaches.

One of the effective decentralization strategies that can facilitate the dissemination of bioethical information to all persons and communities is the integration of bioethical principles into all healthcare sectors, leading to the establishment of healthcare bioethics. A devolutionary strategy can be used to achieve this. The usage of a devolution strategy can concentrate on developing new or improving already existing local healthcare bioethical practices to ensure decentralized implementation of the principles and aims of bioethics. It is necessary to develop bioethical training for all local healthcare stakeholders. Following bioethical training, all local healthcare stakeholders should assume the regular duties of disseminating bioethical knowledge to all people and communities. Because they frequently engage with communities and different people, community health professionals ought to be one of the target populations for bioethical training. It is also possible to disseminate bioethical information to all people and communities through other forms of decentralization, such as deconcentration, delegation, and privatization, but this should be done with caution because these methods might not result in sustainability and comprehensibility.

Institutional criteria: Different institutions must be enthusiastic and invest significant energy in terms of using bioethical principles all the time in all of their actions to improve people’s dignity, rights, and health status. Thus contribute to strengthening the health system. The teaching of bioethics has been confined to tertiary institutions [44]. However, in some countries, there have been some proposals to teach bioethics in secondary schools, but it is not clear whether such proposals were implemented. Until now, few proposals have been made regarding the teaching of bioethics in primary schools and communities.

The human brain is like fertile land. Sow good seeds and bad seeds in fertile land; all of them germinate. This is like the human brain because it can perceive and store all good and bad conduct from surrounding environments. There is a common proverb in Kinyarwanda that says, Igiti Kigororwa kikiri gito, in English; a tree is straightened while still young. Ethics focuses on teaching about good and bad conduct. It may also refer to the application of values and moral rules to human activities [45]. Bioethics is an applied branch of ethics [31,45] that aims to empower people’s right conduct (wisdom) in order to improve their quality of life. It is better to start getting such wisdom in early childhood. Otherwise, it is very hard to straighten some adult people who have adopted bad behaviors in their actions for many years. This could be a reason why ethics is comprehensively taught to numerous adult people in tertiary institutions, but some still adopt wrong conduct during their working periods. For instance, almost all clinical bioethics is taught to all health-related students. But truly, not all of them apply ethical principles in their working lives after becoming health professionals. Some harm themselves, and some harm their clients. The aim of Article 2 of the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights decrees that we must “safeguard and promote the interests of the present and future generations” [25]. In fact, we must use the cheapest approaches for protecting the interests of future generations. One of those approaches is to design ways of teaching bioethics to all people, but mainly to young generations.

Ethical inquiry-based criteria: Based on ethical inquiry criteria, three components that make up the healthcare bioethical system are shown in Figure 3. Ethical inquiries must be used to in order deliver wisdom to all people to gain optimal health status. In turn, if such status has been attained, ethical inquiries must be used in order to inspire people to adopt strategies that aim at ensuring the stability of such a state. Normative-based healthcare bioethics should direct its focus on the identification of the proper course of action that is in line with human moral, correct, or just ways of thinking and acting to improve people’s health status and well-being. Factual or descriptive-based healthcare bioethics should direct its focus on inspiring people to apply techno-scientific knowledge in conjunction with moral principles as ways of applying proper courses of action that are in line with humans’ behaviors and moral, correct, and proper ways of thinking and acting in the direction of improving people’s health status and well-being. Conceptual-based healthcare bioethics encompasses the entire logical alignment and connotations of anything and everything to the foremost thinking, configurations, plans, practices, and implementation of the proper course of actions centered on humans’ behaviors and moral, correct, and proper ways of thinking and acting in the course of improving people’s health status and well-being.

Life-sustaining factor-based criteria: Considering major life-sustaining factors, two components that comprise healthcare bioethics are shown in Figure 2. All people should morally respect the natural beauty of the world in order to maximize their health. The natural beauty of the world is composed of biotic and abiotic components. Interactions between biotic and abiotic factors make life possible in the world. Biotic refers to living things. These include organisms from the five kingdoms of living things, namely, Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, Monera, and Protista. Such respects may encompass, for instance, avoiding illegal and unethical hunting of wild animals. Such respect may add considerable benefits to human health by preventing many zoonotic diseases (including epidemics and pandemics such as Salmonellosis, Brucellosis, Plague, Rabies, Ebola, Avian Influenza, etc.).

Abiotic factors refer to non-living things. Examples of abiotic factors include water, air, soil, the atmosphere, etc. Setting abiotic factor-based healthcare bioethics is highly needed to ensure the attainment of maximal human health. Various ethical values related to abiotic factors must be developed. Values that encompass, for instance, avoiding soil degradation and water and air pollution are needed. Having these values may help minimize hunger and poverty, various cancers, and airborne infectious diseases. Moral values are more needed in order to stop the contamination of the atmosphere than anything else globally. Such moral values may include empowering all people to stop releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Abnormal climate change has been negatively affecting human health in unacceptable ways. However, unethical means to support people to be resilient to those impacts are still suboptimal, and in fact, people continue to pursue activities that further contaminate the atmosphere. For instance, in one of the side events of the Conference of the Parties (COP 27), it was revealed that unmanaged waste is a hidden cause of abnormal climate change and that 10% of greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere are from the waste sector. People may not be aware of this fact because, in many countries, people haphazardly dump unmanaged waste everywhere, yet evidence shows that such dumping contributes to about 31% of the 10% of greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere. Dumping waste haphazardly is unhealthy and unethical. Essentially, ethical principles are needed to maximize all motivations that aim to slow down the occurrence of abnormal climate change. Moreover, ethical principles are needed in order to support people’s resilience to health-related problems associated with abnormal climate change.

Functions of healthcare bioethics

The world we want needs bioethics because bioethics is the science of survival and a bridge to the future. The world we want needs bioethics because bioethics is the love of life [3]. The world we want needs bioethics because bioethics is life for all. The world we want needs bioethics because bioethics focuses on the fact that a suitable ecosystem and climate are essential to achieve life for all. The world we want needs bioethics because bioethics empowers people to use scientific knowledge and technologies in the right ways in order to improve their quality of life. The world we want needs bioethics because it focuses on respecting all humans’ dignity, health, and rights. Firmly, bioethics can support the achievement of the MDGs and SDGs. All SDGs integrate with each other. SDG 3 focuses on ensuring healthy lives and well-being for all [46]. Specifically, the world we want needs healthcare bioethics because healthcare bioethics can support achieving SDG 3 and thus health for all. We must teach people to embrace the right conduct in all of their actions. This is the most powerful and cheapest way to ensure civilization. Thus, we enable people to make sense of the world and improve their quality of health. We must respect the principles of healthcare bioethics because they may help us reach the world we want. In any country, good governance is needed in order to achieve the goals and activities taking place in healthcare bioethics.

Those who want evidence about the power of ethics in terms of advancing people’s health and mastering how to apply ethical principles to improve people’s lives should visit Rwanda. Post-genocide, the Government of Rwanda committed to enhancing good governance and leadership, unity, and reconciliation [47–50] and such approaches have upgraded Rwanda and its population to a suitable level of worthy living. Truly, optimal recognition and use of ethical principles have been the main guiding approaches for Rwanda in order to achieve all those. Itorero Ry’ Igihugu (launched in 2009 by His Excellency, Paul Kagame, the president of the Republic of Rwanda) and the Ndumunyarwanda program are examples of programs that the Government of Rwanda used to promote the use of ethical principles by all Rwandans. The beauty of these programs is that they target all Rwandans. Numerous signposts that contain different ethical values have been established throughout the country. Among other things, ethical values focused on in Itorero Ryigihugu and found in those signposts include 1) unity, 2) patriotism, 3) selflessness, 4) integrity, 5) responsibility, 6) volunteerism, and 7) humility. One of the functions of those signposts is to remind all Rwandans to maximize right conduct in all of their actions. Activities that entail improving Rwandans’ health status have been greatly emphasized. One example of such conduct says that “Kirazira Kugira Umwanda”, in English, means it is prohibited to have an unhygienic state. The outcomes of Rwanda’s good leadership, adoption of all those ethical values, and other commitments have improved the quality of life for all Rwandans. For instance, as of 2023, the life expectancy in Rwanda is 70.00 years, compared to 26.45 years in 1994 and under 50.00 years for all the years between Rwanda’s postcolonial periods (after 1962) and 1994. Based on these facts, the author firmly declares that bioethics is very important in terms of improving people’s lives. As stated earlier, healthcare bioethics is a branch of bioethics that focuses on the application of ethical principles as a mechanism of wisdom enhancement in regard to dialogues and decision-making related to healthcare events and situations. Its functions are numerous at all levels and entail improving the health status of all human beings. Table 1 provides some functions of healthcare bioethics at different levels in terms of improving the quality of life of human beings.

| Table 1: Showing some functions of healthcare bioethics. | |

| Levels | Contributions of healthcare bioethics |

| Healthcare clients' lives |

|

| Healthcare teams and direct Healthcare provision at institutional levels |

|

| At policy-making, health, and ethical-regulating institutional levels |

|

| At the education level |

|

| At health-related research organizations |

|

| At the ecosystem level |

|

| National, Regional, continental, and Global levels |

|

Pre-standard and standard practices of healthcare bioethics

To advance bioethics, it is critical to establish and share norms, rules, good practices, and laws. In all branches of bioethics, those norms, rules, good practices, and laws must be used as mechanisms of wisdom enhancement in order to upgrade the quality of life of all people globally. All these require meticulous planning, monitoring, implementation, forecasting, and standard strategies. Pre-standard and standard practices still exist in the field of bioethics, partly because it is a relatively new discipline. Accordingly, the World Health Organization has adopted six pillars to strengthen the modern universal health care system. The six pillars of WHO strength are: 1) governance: management and accountability; 2) finance: funding availability and allocation; 3) service delivery: accessibility, affordability, and acceptability; 4) human resources: recruitment, retention, development, and deployment; 5) information systems: data quality, analysis, dissemination, and use; 6) Medicine and supplies: accessibility, quality, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness [51,52]. Healthcare bioethics has been lacking among these pillars; however, healthcare Bioethics may be a vital branch of bioethics and a new possible pillar for modern healthcare systems to strengthen worldwide. All actions taking place in healthcare bioethics can synergize all the WHO pillars of strength. To ensure objective, effective, and efficient implementation of the activities to take place in healthcare bioethics, it is critical to differentiate between pre-standard and standard practices of healthcare bioethics. Though not exhaustive, Table 2 demonstrates pre-standard and standard practices in healthcare bioethics.

| Table 2: Showing Pre-Standard and Standard Practices in Healthcare Bioethics. | ||

| Pre-standard practices in healthcare bioethics | Standard practices in healthcare bioethics | |

| Definition | Pre-Standard practices in Healthcare Bioethics refer to the old-style and inaccurate planning, monitoring, implementing, and forecasting for the activities to take place in healthcare bioethics (otherwise standards do not exist in such a way). | Standard practices in health care bioethics refer to an updated style and accurate planning, monitoring, implementing, and forecasting strategies for the activities to take place in healthcare bioethics. |

| Planning for activities to take place in healthcare bioethics | Centralized, centered planning strategies | Centralized and decentralized-centered planning approaches |

| Absolutely institutional-oriented planning approaches | Community-oriented planning approaches are considered. | |

| Where teaching bioethics is the main planned activity (lesson), tertiary health-related institutions are mainly targeted and planned for (i.e., Primary and secondary schools are not considered). | Where teaching bioethics is the main planned activity (Lessons), tertiary health-related institutions are mainly targeted and planned for (i.e., primary and secondary schools must be considered). | |

| Inadequate financial planning and funding to support the implementation strategies of the planned healthcare bioethical-related activities | Adequate financial planning and funding to support the implementation strategies of the planned healthcare bioethical-related activities | |

| There is no sufficient plan for the recruitment of adequate Human resources to support the implementation of the planned activities. | The plan for the recruitment of adequate Human resources to support the implementation of the planned activities is done well and sufficiently. | |

| Planning strategies are illogical and incoherent. | Planning strategies are logical and coherent. | |

| Planning has no concepts or doctrines that clarify the standards. | Planning has concepts and principles that clarify the standards and why | |

| It does not describe, explain, or make specific predictions. | It describes, explains, and makes specific predictions. | |

| Planning has no specific domain where it applies (otherwise, planning is generalized). | Planning has a specific domain where it applies; otherwise, planning is specifically centered on specific activities or ambitions. | |

| Planning is not based on empirical data. | Planning is based on empirical data. | |

| Activities related to respecting biotic and abiotic factors are not planned for (i.e., The plan only targets humans). | Activities related to respecting biotic and abiotic factors are planned for (i.e., the plan does not only target humans). | |

| Implementation of activities to take place in healthcare bioethics | The top-down approach is mainly used in the implementation of the planned healthcare bioethical-related activities. | Both the bottom-up and top-down approaches is used in the implementation of the planned healthcare bioethical-related activities. |

| No timely implementation of the planned healthcare bioethical-related activities | Timely implementation of the planned healthcare bioethical-related activities | |

| Sometimes there is no implementation of the planned healthcare bioethical-related activities. | Always, implementation of the planned healthcare bioethical-related activities is accomplished. | |

| Insufficient implementation of activities relevance, effects, and efficiency | Sufficient implementation of activities relevance, effects, and efficiency | |

| Inadequate Human resources to implement planned activities | Adequate Human resources to implement planned activities | |

| Community participation and involvement are not considered in implementing processes for activities planned to take place in healthcare bioethics. | Community participation and involvement are considered in implementing processes for activities planned to take place in healthcare bioethics. | |

| Monitoring of activities to take place in healthcare bioethics | Concepts, moral principles, and strategies followed to monitor healthcare bioethical-related activities are not substantive enough to enable the prediction of future healthcare bioethical events or activities. | Concepts, moral principles, and strategies used to monitor healthcare bioethical-related activities are substantive enough to enable the prediction of future healthcare bioethical events or activities. |

| Non-enhanced results and reports sharing strategies for the monitored healthcare bioethical-related activities | Enhanced results and reports sharing strategies for the monitored healthcare bioethical-related activities | |

| Monitoring is not done at regular periods. | Monitoring is done at regular periods. | |

| Sometimes monitoring of activities taking place in healthcare bioethics is not considered all the time. | All activities taking place in healthcare bioethics are monitored all the time. | |

| Forecasting for improving activities that take place in healthcare bioethics | Forecasting strategies do not consider the change in existing ethical theories, principles, and practices. | Forecasting strategies do consider the change in existing ethical theories, principles, and practices and emphasize creating better theories than existing theories. |

| Forecasted activities are not general enough to be applicable in several ethical settings. | Forecasted activities are general enough to be applicable in several ethical settings. | |

| Forecasted healthcare bioethical activities are insufficiently practical and will not result in the forecasted outcomes. | Forecasted healthcare bioethical activities are sufficiently applicable and, if applied by way of forecast, will result in the forecasted outcome. | |

| Forecasted healthcare bioethical activities are set in concrete. | Forecasted healthcare bioethical activities are not set in concrete. | |

| Revision and improvement are not based on standard ethical practices. | Revision and improvement are based on standard ethical practices. | |

| Forecasted ethical activities are not in order to make sense of the moral phenomena related to health in the world. | Forecasted ethical activities are necessary to make sense of the moral phenomena related to health in the world. | |

Healthcare bioethics is very important. The goal of this article has been to describe healthcare bioethics in terms of its description, branches, core principles, functions, components of the healthcare bioethics system, and pre-standard and standard practices in healthcare bioethics. According to the best knowledge of the author, this is the first paper that has attempted to describe healthcare bioethics. Principles of bioethics must be integrated into all healthcare sectors to eliminate or minimize several of the ephemeral and heuristic approaches that are still hindering the achievement of optimum health status for some global populations. It is convenient and logical to affirm that all people worldwide must sufficiently profit from healthcare-related bioethics knowledge. Unfortunately, after many years of the existence of bioethics, implementing its goals and principles remains centralized and confined to academic fields. What remains unknown is how to implement the goals and principles of bioethics in decentralized manners so that all people get benefits related to bioethics. Further studies are required to determine the best options for effective and efficient implementation of the goals and principles of bioethics in decentralized manners so that all people get benefits related to it. Integrating bioethical principles in all healthcare sectors to result in the formation of healthcare bioethics is among the powerful decentralization approaches that can support the delivery of bioethical knowledge to all individuals and communities. This can be done via deconcentration, devolution, delegation, and privatization strategies. It will be very useful to investigate which strategy is cost-effective, effective, and efficient in terms of delivering bioethical knowledge to all individuals and communities.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2022). World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. UN DESA/POP/2022/TR/NO. 3.

- General Assembly Economic and Social Council ADVANCE UNEDITED Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals : 2023 May.

- Martins PN. A Concise Study on the History of Bioethics : Some Reflections. Middle East J Bus. 2018;13(1):35–7.

- Ambrose CT. Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) - an unfinished life. Acta Med Hist Adriat. 2014;12(2):217-30. PMID: 25811684.

- Ages M. What was medieval and Renaissance medicine? 2022;1–16.

- Kapp KA, Talboy GE. John Hunter, the father of scientific surgery. 2017;34–41.

- Dunn PM. Dr Edward Jenner (1749-1823) of Berkeley, and vaccination against smallpox. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1996 Jan;74(1):F77-8. doi: 10.1136/fn.74.1.f77. PMID: 8653442; PMCID: PMC2528332.

- Melville W, Fazio XE. The Life and Work of John Snow. 2014 (January 2007).

- Santosa A. Where are the world’s disease patterns heading? The challenges of epidemiological transition. 18 edition. Vol. 3. Newyolk: McGraw Hill; 2010; 1–14. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2882287&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract

- McKeown RE. The Epidemiologic Transition: Changing Patterns of Mortality and Population Dynamics. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2009 Jul 1;3(1 Suppl):19S-26S. doi: 10.1177/1559827609335350. PMID: 20161566; PMCID: PMC2805833.

- Omran AR. The epidemiologic transition theory revisited thirty years later. World Heal Stat Q. 1998;51(2–4):99–119.

- Janvier N. African Countries being categorized as developing countries should not be an excuse for having a Weak / Poor Health System. 2022;10(5):2119–24.

- National Research Council (US). The Continuing Epidemiological Transition in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2012. PMID: 23230581.

- CDC A. Africa CDC Non-Communicable Diseases, Injuries Prevention and Control and Mental Health. Africa CDC. 2022.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF W and W. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Urbanization, agrifood systems transformation, and healthy diets across the rural-urban continuum. Rome, FAO. 2023.

- Callahan D, Lamm E. Global Bioethics: What for? 20th anniversary of UNESCO’s Bioethics Programme. UNESCO. 2015.

- WHO. World health statistics 2019: Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2019.

- WHO. World health statistics 2020: Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2020.

- Have JHAMJ ten, S. M, editors. The UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights Background, principles and application. Paris: UNESCO Publishing; 2009.

- Zanella DC. VR Potter's Global Bioethics. 2019;22(1998).

- Furnari MG. The scientist demanding wisdom: the "Bridge to the Future" by Van Rensselaer Potter. Perspect Biol Med. 2002 Winter;45(1):31-42. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2002.0007. PMID: 11841029.

- WHO. The Right to Health. WHO Press. 31.

- Clift C, Clift C. The Role of the World Health Organization in the International System Centre on Global Health Security Working Group Papers The Role of the World Health Organization in the International System. R Inst Int Aff. 2013;44(February):0–53.

- CESCR General Comment No. 14: The Right to the Highest Attainable Standard of Health (Art. 12). 2000;2000:14.

- UNESCO. Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights. Law Hum genome Rev = Rev derecho y genoma Hum / Chair Law Hum Genome, BBV Found Gov Biscay, Univ Deusto. 2005;(23):227–37.

- Sustainable T, Goals D. The Sustainable Development Goals Report. UN. 2022.

- Global Network of WHO Collaborating Centres for Bioethics: progress report 2017-2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2018.

- WHO. Global Network of WHO Collaborating Centres for Bioethics. WHO. 2021;2023:1–3. Thirteenth general programme of work 2019-2023 (who.int)

- Pikoulis Emanouil, Waasdorps Christine, Lepranieemi Ari BD. Hippocrates: The True Father Of Medicine.

- Antoniou GA, Antoniou SA, Georgiadis GS, Antoniou AI. A contemporary perspective of the first aphorism of Hippocrates. J Vasc Surg. 2012 Sep;56(3):866-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.05.002. PMID: 22917047.

- Rajput V, Bekes CE. Ethical issues in hospital medicine. Med Clin North Am. 2002 Jul;86(4):869-86. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(02)00013-5. PMID: 12365344.

- Takala T. What is wrong with global bioethics? On the limitations of the four principles approach. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2001 Winter;10(1):72-7. doi: 10.1017/s0963180101001098. PMID: 11326789.

- Nzayikorera J. Existence Of Unequal Treatment in Healthcare : An Indicator for The Violation of Healthcare Bioethical Principles. Glob Bioeth Enq. 2023;11(June 1993):12–27.

- Sartorious N. The meaning of health and its Promotion. Rev Med Chil. 2006;89:539–48.

- Bankowski Z. Medical ethics. World Health. 1989 April.

- Bioethics GN of WCC for. Global Health Ethics Key Issues. WHO Libr. 2015.

- Neil C. Manson, Onora O N. Rethinking Informed Consent In Bioethcs. Cambridge University Press. 2007.

- Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L, Alkire BC, Alonso N, Ameh EA, Bickler SW, Conteh L, Dare AJ, Davies J, Mérisier ED, El-Halabi S, Farmer PE, Gawande A, Gillies R, Greenberg SL, Grimes CE, Gruen RL, Ismail EA, Kamara TB, Lavy C, Lundeg G, Mkandawire NC, Raykar NP, Riesel JN, Rodas E, Rose J, Roy N, Shrime MG, Sullivan R, Verguet S, Watters D, Weiser TG, Wilson IH, Yamey G, Yip W. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet. 2015 Aug 8;386(9993):569-624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X. Epub 2015 Apr 26. PMID: 25924834.

- Ng-Kamstra JS, Greenberg SLM, Abdullah F, Amado V, Anderson GA, Cossa M, Costas-Chavarri A, Davies J, Debas HT, Dyer GSM, Erdene S, Farmer PE, Gaumnitz A, Hagander L, Haider A, Leather AJM, Lin Y, Marten R, Marvin JT, McClain CD, Meara JG, Meheš M, Mock C, Mukhopadhyay S, Orgoi S, Prestero T, Price RR, Raykar NP, Riesel JN, Riviello R, Rudy SM, Saluja S, Sullivan R, Tarpley JL, Taylor RH, Telemaque LF, Toma G, Varghese A, Walker M, Yamey G, Shrime MG. Global Surgery 2030: a roadmap for high income country actors. BMJ Glob Health. 2016 Apr 6;1(1):e000011. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000011. PMID: 28588908; PMCID: PMC5321301.

- Alkire BC, Raykar NP, Shrime MG, Weiser TG, Bickler SW, Rose JA, et al. Global access to surgical care: A modelling study. Lancet Glob Heal. 2015;3(6):e316–23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70115-4

- Information UD of P. The Millennium Development Goals. United Nations. 2015; 2015.

- Johnston RB. Arsenic and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Arsen Res Glob Sustain - Proc 6th Int Congr Arsen Environ AS 2016. 2016;12–4.

- Holm S, Williams-Jones B. Global bioethics – myth or reality? 2006;10:1–10.

- Fischer ML, Roth ME, Martins GZ. Path of Dialogue : A bioethics experience in primary school. 2017;25(1):89–100.

- Iserson KV. Principles of biomedical ethics. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1999 May;17(2):283-306, ix. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70060-2. PMID: 10429629.

- Plan GA, Lives H. What worked? What didn’t? What’s next? 2023 progress report on the Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2023.

- Ibrahim N. Leadership and Good Governance : The Rwandan Experience. Int J Res Innov Soc Sci. 2019;III(Ii):68–78.

- Anastase M. Rebuilding After Conflict And Strengthening Fragile States: A view From Rwanda. 2012;128.

- Allen-Storey C. Policy brief: Unity and reconciliation in Rwanda: A look at policy implications vis-à-vis social cohesion. Int Alert - Rwanda. 2018.

- National Strategy Framework Paper on Strengthening Good Governance For Poverty Reduction In Rwanda. 2002.

- WHO. Everybody’s business strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes who’s framework for action. WHO Libr Cat Data. 2007.

- WHO. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: A handbook of indicators and their measurements strategies. WHO Libr Cat Data Monit. 2010.